How Obi works

You're not gonna regret it, the payoff is huge!

Obi models everything as a set of particles (freely moving lumps of matter) and constraints (rules that control particle behavior), using a simulation paradigm known as position-based dynamics or PBD for short.

In PBD, forces and velocities have a somewhat secondary role in simulation, and positions are used instead. Its main advantage compared to traditional, velocity-based simulation methods is that it is unconditionally stable.

Stability

What exactly do we mean by "unconditionally stable"? we mean the simulation can't blow up due to specific conditions that commonly take place in games. But why do most physics engines occassionally cause objects to behave spastically or yeet themselves into oblivion, and why is Obi supposed to be immune to this? To find out, let's build a simple, traditional physics engine and put it to the test:

A physics simulation involves calculating how some object properties - such as position or velocity - change over time. Time is a continuous variable, however computers are digital: this means they cannot represent truly continuous data and must chop it into small chunks of finite size. For this reason, when performing a physics simulation we divide time into timesteps, similar to how we divide time into frames during rendering. (See update loop for details on how simulation and rendering fit together).

Armed with this knowledge, let's move an object from one timestep to the next according to its velocity. To do this, we just need to remember that velocity is the rate of change in position over time:

position += velocity * timestepDuration;

Easy enough. If we wanted to also update its velocity (for instance, due to some external acceleration such as gravity), we just need to remember that acceleration is the rate of change in velocity over time:

velocity += gravityAccel * timestepDuration; position += velocity * timestepDuration;

That's it: we just built a physics engine, capable of simulating one object using numerical integration. Now for the fun part: we'll take this object and attach it to a point in space using a spring.

The force applied by a spring is simply Stiffness x Deformation. Deformation is the difference between the spring's current length and its rest length.

For simplicity's sake let's also assume the object's mass to be 1. Since Force = Mass x Acceleration, force equals acceleration and Acceleration = Stiffness x Deformation.

currentSpring = attachedPoint - position; deformation = currentSpring - restLenght * currentSpring.normalized; springAccel = stiffness * deformation; velocity += (gravityAccel + springAccel) * timestepDuration; position += velocity * timestepDuration;

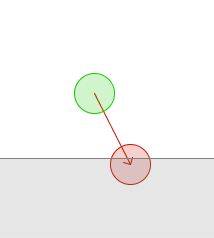

Let's use a timestepDuration of 0.016 seconds and stiffness value of 200, then execute this code in a loop drawing the spring and the object at the end of each timestep:

That's a nice pendulum. Now let's crank up the spring's stiffness to 16000, hoping to eliminate bounciness:

Oops! the reason for such spectacular failure is that the acceleration induced by our extra-stiff spring is very large. Since velocity is only updated once during each timestep, the simulation cannot react to fast changes in velocity: the object *zooms* towards its target position but blazes past it. When we arrive at the next timestep, the spring is even more stretched so it attemps to go back to its rest length by applying an even larger acceleration to the object: with every passing timestep, the situation gets worse and the simulation diverges over time, becoming unstable.

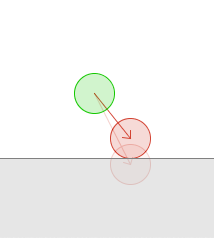

To avoid overshooting we need to update the simulation more often, by using a timestep duration of 0.005 seconds:

This is no good since large velocities (which are common in games) force us to update physics more often to maintain stability, which has an impact on performance. What's worse, using smaller timesteps doesn't guarantee stability: it just gives us more headroom before the simulation falls apart.

In case we couldn't afford to calculate many small timesteps, we'd need to manually clamp masses and forces in our game to make sure there's no large velocities and things don't blow up. The situation becomes a nightmare when the complexity of our simulation increases and players are able to interact with it, since calculating artificial limits is not easy anymore and solving stability issues requires us to use an absolutely tiny timestep. Such is the case of the following multiple pendulum:

Is there a simple, robust alternative that always behaves gracefully regardless of timestep duration and simulation complexity? Fortunately, there is:

Position-based dynamics

At the beginng of every timestep Obi predicts a new, tentative position for each particle, according to its velocity and the simulation's timestep duration. This tentative position probably violates many constraints: it could be inside a collider, or far away from where a spring needs it to be.

// apply external accelerations such as gravity, then calculate a tentative position: velocity += acceleration * timestepDuration; tentativePosition = position + velocity * timestepDuration;

This position needs to be adjusted so that it meets all conditions imposed by the constraints affecting that particle. We then calculate the velocity that would take the particle from its current position to the tentative position:

// adjust tentative position: tentativePosition = validPosition; // calculate the velocity that would take us there: velocity = (tentativePosition - position) / timestepDuration;

Finally, we move the particle to its new position:

// move the particle: position = tentativePosition;

We perform these 3 steps process every timestep -predict tentative position, correct tentative position, advance to corrected position-. Advancing multiple timesteps we get something like this:

Using this method we can formulate our spring as a positional constraint instead of a force, by simply moving the object to a position that does not deform the spring: we only adjust positions, velocities are calculated from them so it's not possible for overshooting to take place.

As a result, the simulation cannot blow up no matter our choice of timestep duration, how violent user input is or how stiff constraints are - they will automatically be as stiff as the timestep duration allows for. Using longer timesteps will yield softer constraints that the simulation can comfortably handle without blowing up.

Obi also allows to specify a maximum desired stiffness, by assigning a compliance value to each constraint. Compliance is the inverse of stiffness, so zero compliance means "as stiff as possible given the current timestep duration". A compliant constraint is soft, a non-compliant constraint is stiff.

So is this method unconditionally stable in practice? Yes, unless coupled with Unity rigidbodies which are NOT unconditionally stable. Unity's rigidbody engine uses the classic force/velocity based approach. This means that collisions against or attachments to rigidbodies may be unstable, because the forces calculated and applied by Obi may not be robustly handled by rigidbody simulation. This may require you to reduce Unity's fixed timestep setting (found in ProjectSettings → Time) and/or reduce the amount of substeps used by Obi, to get both engines performing simulation at a similar frequency.

Iterations

Each constraint in Obi takes a set of particles and (optionally) some information about the "outside" world as input: colliders, rigidbodies, wind, athmospheric pressure, etc. Then it modifies the particles' positions so that they satisfy a certain condition.

Sometimes, enforcing a constraint can violate another, and this makes it difficult to find a tentative position that meets all constraints at once. Obi will try to find a global solution to all constraints in an iterative fashion. With each iteration, we will get a better solution, closer to satisfying all constraints simultaneously.

There's two ways Obi can iterate over all constraints: in a sequential or parallel fashion. In sequential mode, each constraint is evaluated and the resulting adjustments to particle positions immediately applied, before advancing to the next constraint. Because of this, the order in which constraints are iterated has a slight impact on the final result. In parallel mode, all constraints are evaluated in a first pass. Then in a second pass, adjustments for each particle are averaged and applied. Because of this, parallel mode is order-independent, however it approaches the ground-truth solution more slowly.

In the following animations, three particles (A, B and C) generate two collision constraints which are then solved. This all happens during a single simulation step:

Each additional iteration will get your simulation closer to the ground-truth, but will also slightly erode performance. So the amount of iterations acts as a slider between performance -few iterations- and quality -many iterations- for that specific type of constraint.

Once all iterations for this timestep have been carried out and the particle position has been adjusted, a new velocity is calculated and we are ready for the next one. Here's an animation showing the complete process over multiple timesteps:

In most cases, larger simulations (those that have more particles and constraints, like long/high-resolution ropes) need a smaller timestep duration or a higher amount of iterations to appear stiff. An insufficient budget will almost always manifest as some sort of unwanted softness/stretchiness, depending on which constraints could not be fully satisfied:

- Stretchy cloth/ropes if distance constraints could not be met.

- Bouncy, compressible fluid if density constraints could not be met.

- Weak, soft collisions if collision constraints could not be met, and so on.

The most effective way to increase perceived stiffness and overall simulation quality is to use a shorter timestep duration. This can be accomplished either by increasing the amount of substeps in your solver, or decreasing Unity's fixed timestep (found in ProjectSettings → Time). Intuitively speaking, taking smaller steps when advancing the simulation causes the tentative position calculated at the beginning of each step to be closer to the valid position we started from. This way, we need less iterations to arrive at a new valid position.

On the flip side, using few iterations and/or a large timestep is absolutely fine when you're looking for stretchy behavior. Instead of increasing constraint compliance (elasticity), simply spend less substeps/iterations: the naked eye cannot tell apart a cheap, low-quality simulation from an expensive, high-quality simulation of a very elastic object.

Unlike other engines, Obi allows you to set the amount of iterations spent in each type of constraint individually. Each one will affect the simulation in a different way, depending on what the specific type of constraint does, so you can really fine tune your simulation.

For this reason, it's best to start by setting all constraint iterations to 1 and the solver's substeps to a value that yields acceptable quality. Once you're happy with the amount of substeps, you may want to spend a few extra iterations on specific constraint types that could use some extra stiffness. You should never need to use more than 2 or 3 iterations for any constraint type.

Takeaway message: If your rope/cloth/softbody/fluid is too stretchy or bouncy, you should try the following:

- Increasing the amount of substeps in the solver.

- Increasing the amount of constraint iterations in the solver.

- Decreasing Unity's fixed timestep.

Mass and constraints

When two bodies are involved in a constraint of any kind (a collision constraint, a distance constraint, etc), the amount of displacement applied to each one depends on their mass: the heavier of the two will be displaced a smaller distance. The reason for this is that Force = Mass x Acceleration. As a result, the change in velocity caused by a force is inversely proportional to the mass of the object: Acceleration (change in velocity) = Force / Mass.

In Obi, you can set the mass of cloth and softbody particles using their blueprint editor, the mass of ropes and rods is set on a per-control point basis using the path editor, and the mass of fluids depends on their density.

Why bother talking about something as ordinary as mass? Because in the context of physics simulation, there's at least 3 common pitfalls associated with it:

#1. Heavier objects do not fall faster

Generally speaking, gravity is a force of attraction between bodies, the magnitude of which depends on the object's masses and the distance between their centers of mass. However when one of the objects is a planet and the other is an comparatively light object that lies on its surface (a car, an apple, you, me), their mass ratio and the distance between them can be considered constant: no matter how heavy an object is, it's not going to skew the balance in its favor against a planet, and no matter how high it goes within the planet's atmosphere the distance between it and the center of the planet won't significantly change.

So for everyday, human-scale affairs taking place on the surface of a planet, gravity is considered an acceleration whose magnitude only depends on the planet you're on (in Earth's case, -9.81 m/s2): the mass of objects does not affect how fast they fall. Air resistance can make lighter objects fall slower though - in Obi you can model this using aerodynamic constraints for ropes and cloth.

#2. The absolute mass of objects does not matter

It's their relative mass that does, often referred to as their mass ratio. In other words: a pair of 20 kg colliding steel boxes would react the same way as a pair of 10 kg wooden boxes. However, it would be far harder for a 10 kg wooden box to move a 20 kg steel box than it would be for a 30 kg cast iron box.

#3. Beware of large mass ratios

Iterative physics engines have a hard time with high mass ratios. As we discussed in the above section, the way Obi deals with many simultaneous constraints is by enfocing them all multiple times (iterating) and accumulating their effect. However when two objects involved in a constraint have a large mass ratio, the heavier one is displaced a very small amount each time the constraint is enforced, which means it may require a lot of iterations for it to meet all constraints simultaneously. So either you spend a lot of iterations and take a performance hit, or you live with partially solved and excessively stretchy constraints: for instance, ropes and cloth that stretch a lot when attached to / colliding with much heavier objects.

Obi uses PBD (position-based dynamics) which means constraints acts on positions while traditional constraints used in other engines act on velocities, but all existing realtime engines iterate over constraints while accumulating their effect on either position or velocity. As a result, the majority of game physics engines are affected by this: PhysX, Unity physics, Havok, Bullet, Box2D, Obi, etc. A rough guideline is that no two objects in your scene should exceed a mass ratio of 1:10, that is, no potentially interacting object should be more than 10 times heavier than another. You can have higher mass ratios, but it will typically require you to increase your solver's budget (iterations/substeps) to ensure constraints are met.

Note there's other types of engine - reduced coordinate solvers, direct solvers, primal descent methods - that are unaffected by large mass ratios, but they have their own kind of limitations and are typically costlier.

Constraint types

Collision constraints

Collision constraints try to keep particles outside of colliders. High iteration counts will yield more robust collision detection when there are multiple colllisions per particle.

Friction constraints

Collision constraints try to reduce the tangential velocity of particles upon collision. High iteration counts will yield more accurate friction calculations.

Particle collision constraints

Identical to collision constraints, but for when collisions happen between particles.

Particle friction constraints

Identical to friction constraints, but for when collisions happen between particles.

Distance constraints

Each distance constraint tries to keep two particles at a fixed distance form each other. These are responsible for the elasticity of cloth and ropes. High iteration counts will allow them to reach higher stiffnesses, so your ropes/cloth will be less stretchy.

Pin constraints

A pin constraint will apply forces to a particle and a rigidbody so that they maintain their relative position. They are created and used by dynamic attachments. High iteration counts will reduce the amount of drift at the pin location, making the attachment more robust.

Stitch constraints

Sticth constraints try to keep 2 particles on top of each other. They are created and used by stitchers. High iteration counts will reduce the amount of drift at the stitch location, making it more robust.

Volume constraints

Each volume constraint takes a group of particles positioned at the vertices of a mesh, and tries to maintain the mesh volume. Used to inflate cloth and create balloons. High iteration counts will allow the ballons to reach higher pressures, and keep their shape more easily.

Aerodynamic constraints

This is the only type of constraint that doesn't have an iteration count. They are always applied only once, that is enough. Used to simulate wind.

Bend constraints

Each bend constraint will work on three particles, trying to get them in a straight line. These are used to make cloth and ropes resistant to bending. As with distance constraints, high iteration counts will allow them to reach higher stiffness.

Tether constraints

These constraints are used to reduce stretching of cloth, when increasing the amount of distance constraint iterations would be too expensive. Generally 1-4 iterations are enough for tether constraints.

Skin constraints

Skin constraints are used to keep skeletally animated cloth close to its skinned shape. They are mostly used for character clothing. Generally 1-2 iterations are enough for skin constraints.

Density constraints

Each density constraint tries to keep the amount of mass in the neighborhood around a particle constant. This will push out particles getting too close (as that would increase the mass) and pull in particles going away (which results in surface tension effects). Used to simulate fluids. High iteration counts will make the fluid more incompressible, so it will behave less like jelly.

Shape matching constraints

Each shape matching constraint records a rest shape for a group of particles, then adjusts their positions so that they maintain this shape as closely as possible. These are used by softbodies.

Stretch/shear constraints

Stretch/shear constraints adjust the position of a pair of particles along the axis of a reference frame, determined by a rotation quaternion. These are used by rods and bones.

Bend/Twist constraints

Bend/twist constraints adjust the orientation of a pair of particles to prevent both bending and twisting. These are used by rods and bones.

Chain constraints

Chain constraints take a list of particles and try to maintain their total length using a direct, non-iterative solver. These are used by rods.